By Neal | June 29, 2021

The EFAIL attacks demonstrate that securing email is hard. Incautious improvements to usability can lead to critical security vulnerabilities. In the case of EFAIL, an attacker could exploit mail clients that show corrupted messages to exfiltrate a message’s plain text.

Although the EFAIL researchers are measured in their response, others, like Thomas Ptacek in his widely cited articles The PGP Problem from 2019, and Stop Using Encrypted Email from 2020, are calling for people to abandon OpenPGP, and give up on secure email. Instead, they argue, people should use secure messengers like Signal.

Thomas’s larger point is simple. Everyone, he says, should “[s]top using encrypted email.” It fails to protect people who have powerful adversaries, and everyone else who uses it is just posing:

Ordinary people don’t exchange email messages that any powerful adversary would bother to read, and for those people, encrypted email is LARP security. It doesn’t matter whether or not these emails are safe, which is why they’re encrypted so shoddily.

- Thomas Ptacek

Thomas is wrong.

As I discuss in detail below, there is a fair amount of evidence that people who have a pressing need can use OpenPGP successfully. For instance, a recent academic paper, When the Weakest Link is Strong: Secure Collaboration in the Case of the Panama Papers, looks at the security practices of the journalists involved in the Panama Papers. The authors found that for over a year, the hundreds of people involved in the project successfully collaborated using OpenPGP.

And there are at least four good reason to protect ordinary people’s email:

-

Email is everyone’s primary trust anchor online.

If a user loses access to an online account, most services have an account recovery mechanism that will let the user back in. Usually, this works by sending an email to the user with a one-time password.

If an attacker compromises a user’s email account, they can use the same mechanism to gain control of the user’s account on any service that uses the email account as a trust root. In practice, that’s most of the user’s online accounts. Unfortunately, two-factor authentication only offers limited protection. It is opt-in and usually uses a phone number, which is easily hijacked.

If account recovery emails were encrypted, the trust anchor would instead be the encryption key. Since the encryption key is stored on the user’s computer, this would defeat this type of attack.

-

Email is prone to phishing.

If companies would digitally sign their emails, then the signatures could be leveraged to better detect phishing. Currently users need to be taught to look for subtle clues to detect this type of attack. This places a high cognitive burden on them, and violates Krug’s first law of usability: “Don’t make me think.”

-

Businesses depend on email.

Even if secure messaging systems offered all the desired workflows that business users need—anecdotal evidence suggests that they don’t—they are walled gardens. This architecture has three major issues, which push businesses back to email:

-

Because some external communication partners will inevitably choose a different, incompatible system, some communication will still occur over the common denominator, email.

-

A walled garden inhibits the creation of custom tools. Businesses need to comply with local legislation. In many jurisdictions, companies need to archive and search messages. Services like Signal don’t support this, and hence aren’t an option.

-

A walled garden not only locks the business into a program, but into a protocol. This makes switching systems very costly. This type of dependency is particularly undesirable for a critical communication tool.

If businesses have to use email, then it would be better if it were secured.

-

-

Privacy.

Even if we reject secure email, people will still use email for privacy-sensitive communication.

Sometimes email is more convenient. Composing and sending long-form content is easier using an email application. So is sending files. Further, although Signal’s group chat feature is great, it needs to be set up and torn down; it is often easier to quickly send an email to a few people.

Other times email is the only option. Most people have a few messaging clients installed on their mobile phone. Nevertheless, it’s not unusual for the only common messaging platform to be email even for small groups.

If ordinary people prefer email, we should figure out how to protect it.

This is not to say that OpenPGP, its various implementations, and the applications that integrate it don’t have problems. They do. The OpenPGP working group needs to finish the cryptographic refresh and finally standardize AEAD. We need email clients that are built with security-oriented workflows for people who have powerful adversaries. And, we need popular mail clients to adopt opportunistic encryption similar to Signal for ordinary users.

It’s true that OpenPGP has been around for three decades. But, unlike Signal, which has received 50 million dollars from one of WhatsApp’s founders, GnuPG’s major donors like Facebook and Stripe have pledged three orders of magnitude less: 50 thousand dollars per year. That’s barely enough to maintain GnuPG never mind do UX research.

It’s time to invest in secure and usable email.

Powerful Adversaries

Critics of OpenPGP often cite the Why Johnny Can’t Encrypt usability study, and followup papers like Why Johnny Still, Still Can’t Encrypt as evidence that OpenPGP is unusable. Yet, a recent multi-year longitudinal study by Borradaile et al., The Motivated Can Encrypt (Even with PGP) suggests that those who have an immediate need can successfully use PGP:

In this research, we ask: How do users with concrete privacy threats respond in the long term to training that aims to overcome the documented usability issues of PGP email encryption? …

[W]e find that the rate of long-term PGP use by our respondents is over 50%, seeming to counter the poor learnability uncovered by laboratory studies. Indeed, in our original PGP email workshops, all but one participant were able to successfully send and receive PGP-encrypted emails.

These results are consistent with a 2017 study of the security practices of the hundreds of participants involved in the reporting on the Panama Papers, When the Weakest Link is Strong: Secure Collaboration in the Case of the Panama Papers. McGregor et al. write that they

were surprised to learn that project leaders were able to consistently enforce strict security requirements—such as two-factor authentication and the use of PGP—despite the fact that few of the participants had previously used these technologies.

These observations match my own from an interview series that I conducted in 2017 with activists and organizations who use GnuPG. I found that many users had defining moments that made OpenPGP’s protection acutely tangible. For instance, in the interview with C5, a digital security trainer from the Philippines, she said:

In one of the communities and networks that I was supporting—let me just say it’s an election, a clean election campaign in Southeast Asia where the leaders of that movement were being arrested or not arrested, [but] detained and then kind of surveilled and all of that. We had to move them away from unsecure communication channels because the communications that they were doing were a lot more substantive than a secure chat software could handle. They needed to exchange documents and files and like lengthy, lengthy kind of messages. We did get them back to email as the main form of communication and then GPG to secure that main form of communication. That really kind of worked. It allowed them to organize and to call for mass demonstrations.

These successes don’t excuse OpenPGP’s poor usability. On the contrary, the studies highlights that a user with sufficient motivation can use OpenPGP despite its poor usability.

Our Primary Online Trust Anchor

According to my password manager, I’ve created an account on hundreds of websites. One thing that nearly all of these services have in common is that they require an email address to create the account.

These services use my email address to update me about the status of a purchase. They sometimes inform me about something they think I’m interested in (“Hey Neal! You bought a refrigerator last week, here are ten other refrigerators you might be interested in adding to your collection!”). And, they use my email address for account recovery.

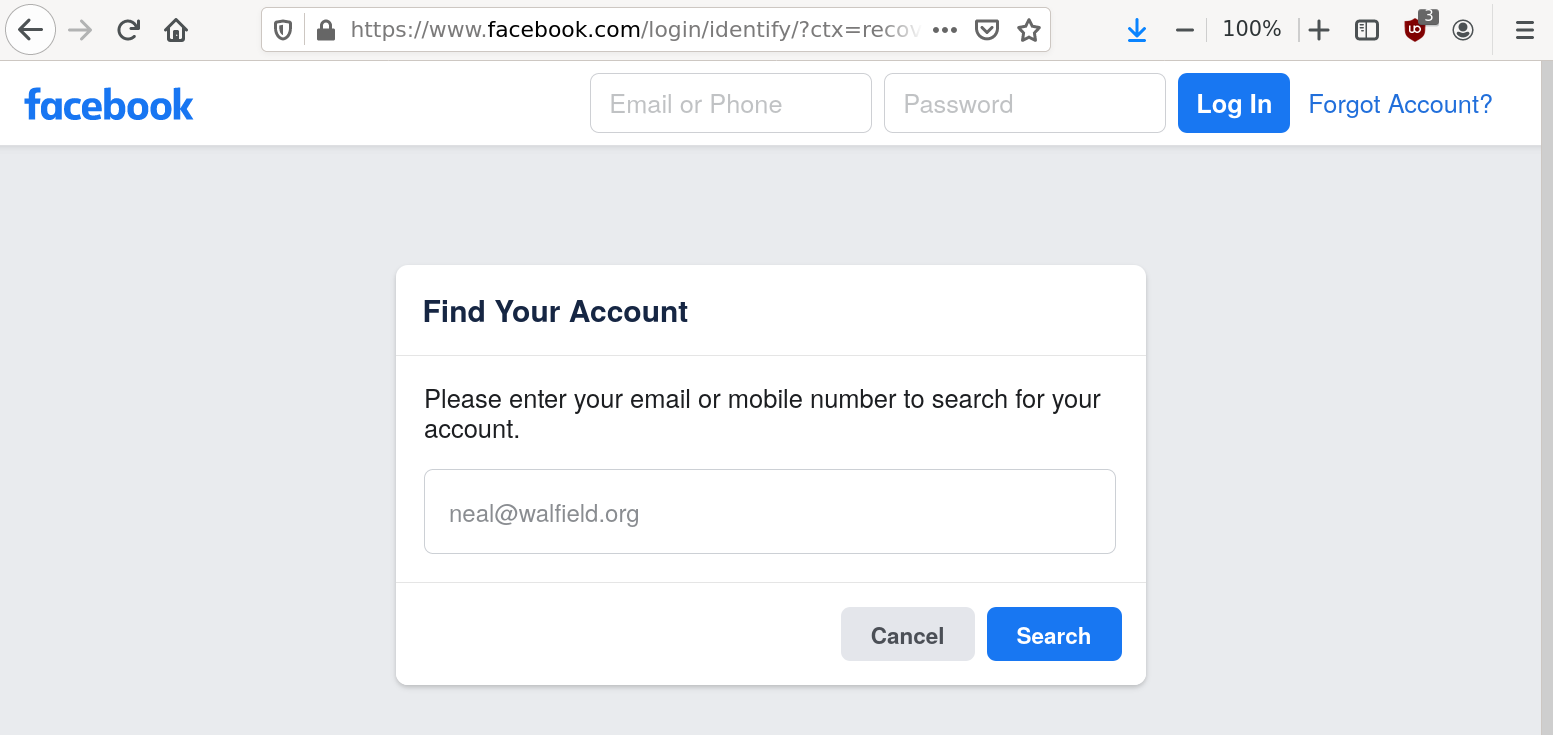

Account recovery usually works as follows. If I’ve forgotten my password, I can use the service’s account recovery tool to request an email. (Facebook’s account recovery tool is shown in the figure.) The email contains a one-time password, which is usually embedded in a link. When I follow the link, I send the one-time password back to the service thereby proving that I control the email address, and thus am the rightful owner of the account.

By allowing me to recover my account using my email address, the service treats my email account as a trust anchor. As many of these services have sensitive personal and financial information about me and the people I interact with, it is essential that I protect it.

Unfortunately, email accounts are taken over on a regular basis. To help protect users, bigger services now offer two-factor authentication. Using two-factory authentication raises the barrier, but it has two major weaknesses as deployed today.

Two-factory authentication’s first weakness is that it is optional. For the general public, banks are the only service that I’m aware of where two-factor authentication is mandatory. By making two-factor authentication opt-in, we guarantee that it remains largely unused.

Jared Spool reports in Do users change their settings? that 95% of users don’t change default settings no matter how bad they are. For instance, early versions of Microsoft Word did not enable autosave. When Jared’s team asked participants why they didn’t enable it, they responded that the developers must have had a good reason not to enable it.

In his recent presentation at USENIX’s Enigma conference, Anatomy of Account Takeover, Google Engineer Grzegorz Milka confirms that this behavior also applies to two-factor authentication, which Google introduced in 2011. As of 2018, less than 10% of Google’s users have enabled it. With this level of adoption, it is almost surprising that this features hasn’t yet been killed by Google. And, Google, because it holds so much user data, is probably an outlier: other services that offer two-factor authentication almost certainly have lower levels of adoption.

The second weakness is that the typical second factor is a telephone number. Using a phone number as a second factor has the big advantage that nearly everyone today has their own; there is no need for users to buy and carry around a dongle. But, phone numbers are susceptible to SIM swapping. Krebs on Security explains how hard this attack isn’t:

[A] series of recent court cases and unfortunate developments highlight the sad reality that the wireless industry today has all but ceded control over this vital national resource to cybercriminals, scammers, corrupt employees and plain old corporate greed.

And the Internet is full of anecdotes from ordinary users like I was hacked, by John Biggs:

At about 9pm on Tuesday, August 22 a hacker swapped his or her own SIM card with mine, presumably by calling T-Mobile. This, in turn, shut off network services to my phone and, moments later, allowed the hacker to change most of my Gmail passwords, my Facebook password, and text on my behalf. All of the two-factor notifications went, by default, to my phone number so I received none of them and in about two minutes I was locked out of my digital life.

In short, control of a phone number as a second factor only offers minimal added protection.

Instead of using the user’s email account as the trust anchor, we could use a cryptographic key. When a service needs to send important data to the user, the service could encrypt it. Then even if the user’s email account and phone number are hijacked, the attacker will not be able to leverage them to also hijack the user’s account on other services. To protect users from local attacks that exfiltrate the secret key material, the secret key material could be stored in a trusted execution environment (TEE) like a TPM or iOS’s Trusted Enclave. This has the advantage that like a phone number most hardware already has a TEE.

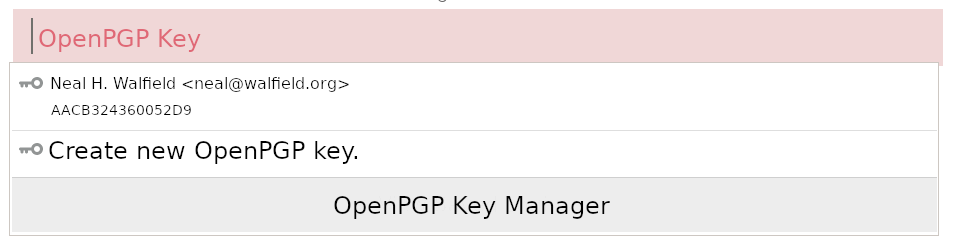

The UX for this uploading an encryption key does not have to be invasive. When the user creates an account, the account creation form could also prompt for an OpenPGP key. If we teach web browsers how to find OpenPGP keys, then the user doesn’t even need to copy and paste a block of text, but can simply select a key from a drop down, as shown in the above figure.

Phishing

Most people I know receive a few phishing emails per week. Many medium and large companies even train their employees to detect such emails, and they regularly test their employees by sending fake phishing mails. If the employees don’t report the phishing email, then they may receive additional training, which is viewed as a punishment.

Having to be on the constant look out for phishing mails increases employees’ cognitive burden. The Greater Manchester Police recently caught a phisher:

Officers in Manchester city centre arrested a man in a hotel yesterday after an estimated 26,000 fraudulent text messages purporting to be a delivery company [Hermes] were sent in one day … asking for bank details after a missed delivery.

Their advice to readers to avoid being scammed was to be vigilant:

Check the address the email has been sent from. By using your mouse to hover over or right-click on the sender name, you will be able to see the email address behind it. Fraudsters often have bizarre email addresses or one that doesn’t quite match with the company they are claiming to be.

Look to see who the email addressed to. Often fraudsters will use an impersonal greeting such as ‘Hi’ or ‘dear customer’.

Don’t feel pressured. Scam emails will often claim there is a time limit or sense of urgency for you to act now, but don’t feel pressured. Take your time to make the checks you need.

Watch out for out for spelling and grammar mistakes. Also look out for slight changes in things such as a website link. This could look very similar to the company’s real website, but even a single character difference means it is leading you to different website.

Think about whether you are expecting an email from that company. If it’s out of the blue, it could be a scam.

This advice is more or less the same advice that the EFF gives:

Some common-sense measures to take include:

- Check the sender’s email address…

- Try not to click or tap!…

- Try not to download files from unfamiliar people…

- Get someone else’s opinion…

It would be nice if we could somehow automate this.

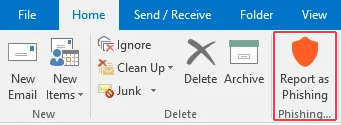

And, yet, we can. If companies would digitally sign their emails, then it would be possible to detect when a signature is missing, or a key cannot be authenticated, or a key is being used for the first time.

Business Requirements

Even if they wanted to, it is unclear if businesses could deprecate email in favor of a secure messaging solution. Businesses need to communicate with other businesses and customers, and whereas email is federated and nearly everyone has an email address, there are many different secure messaging solutions, and all of the popular ones are closed systems. As long as the many different secure messaging solution don’t interoperate, businesses will continue to use email.

This raises another issue: because the popular secure messaging solutions are all walled gardens, shifting critical communication to something like Signal not only locks a company into a particular product, but also a protocol. This makes it even harder for the business to switch should the secure messaging system become undesirable.

But it is not clear what businesses can replace email with a secure messaging solution. Businesses need to comply with regulations. If the secure messaging applications don’t support the required functionality, and that functionality can’t be added due to the closed ecosystem, then secure messaging is not even an option.

HIPAA stands for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. It is a set of laws in the US that address how health information must be handled. The Hipaa Journal explains some of the requirements for sending protected health information electronically. In particular, the data must be sent using end-to-end encryption, and all communication needs to be retained.

Similar regulation applies to other industries in the US. Intradyn, a maker of email archiving software, explains that in the US

[i]n 2006, a law was passed mandating data archiving. According to this set of email archiving regulations, your business needs to maintain electronic records. That means that you can’t just delete emails when they are no longer currently relevant; they need to be stored for long-term access. The law requires you to know where that data is stored, to be able to search through it, and to be able to retrieve it on demand. Email archiving isn’t just a convenience, in case you discover that the data would have helped you later; it’s a legal necessity.

The law is also careful to note that simply storing the data isn’t enough. You can’t use a random system, let your emails pile into it, and hope that you never actually have a reason to search through it. Instead, the law notes that you have to know how the system works, be able to use it efficiently, and be able to produce the requested emails quickly. “I don’t know how to get to it” or “It’s not pulling up in a search” isn’t an acceptable excuse anymore.

It seems inevitable that businesses will continue to use email. In that case, then it is sensible to offer it the best technological protection we can. And we can to better than hop-to-hop encryption.

Privacy

Despite secure messaging’s popularity, there are still a number of practical reasons to prefer email. Secure messengers are optimized for real-time chat on mobile phones. Thus, some workflows are easier using email clients. Further, since all of the popular secure messengers are walled gardens, they are unlikely to ever completely dislodge email’s dominance, and email will remain the common denominator.

Although I usually prefer using a real-time chat system to sending an email, there are several situations where email continues to excel from a user experience perspective.

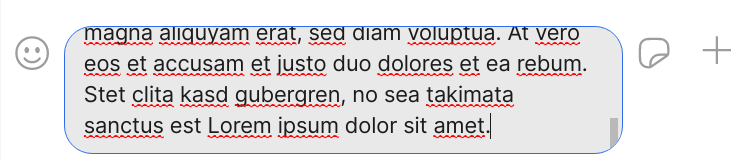

First, it is much more convenient to write long-form content using a proper text editor, than with the tiny text input field that most messengers provide. The figure shows the text input field in Signal’s desktop client (v5.3.0). Only four and a half lines of text are displayed by default.

Another usability issue has to do with exchanging files. Although it is relatively straightforward to send a file using a secure messenger, because most people only have the messaging app installed on their phone, files often need to be transferred to and from the user’s desktop or laptop. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is often done using email, or a file transfer service like Dropbox.

Starting a short-lived group thread is also easier using email. In Signal, for instance, it is first necessary to create a group. If the group stays around, then it clutters the conversation overview. If the group is disbanded too soon, then the user might miss replies. Email’s cc functionality and threading model are often more convenient.

Groups communication has another problem. In my experience even in small groups the only common platform is email.

One could imagine different clients and special tools catering to different needs, and interoperability between different messaging platforms. But at least Signal is not interested in supporting federation never mind alternative clients. Moxie has stated:

I understand that federation and defined protocols that third parties can develop clients for are great and important ideas, but unfortunately they no longer have a place in the modern world.

- Moxie MarlinspikeIf we don’t secure email, then we are left with hop-by-hop encryption. It’s better than nothing, but there are still too many spots where eavesdroppers can listen.

Most people living in liberal democracies will never need to protect their communication from a powerful adversary. But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t create tools to protect their privacy. On the contrary, democracy needs privacy.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I’ve listed several reasons why we should continue to press for secure email for both people who have powerful adversaries, as well as ordinary people. In short: secure messengers are great, but they don’t replace email and will likely never be able to.

Email has staying power, because users are in control (at least, they have more control than with centralized walled gardens). It has been around since the birth of the Internet nearly half a century ago. And, it is closest thing we’ve got to long-term messaging infrastructure.

For businesses and large organizations it is unfathomable to switch their mission-critical communication to a centralized, closed solution that can change in uncontrolled and unexpected ways. Even if they use a Big Tech e-mail service like GMail or Office365, businesses and organizations can still switch providers if their current one starts doing something undesirable—while remaining seamlessly in contact with their customers and everyone else. That’s impossible with Signal, because of Moxie’s decision. And, it is unthinkable in WhatsApp, because it goes against the very core of their business model.

Given that the continued use of email remains inevitable in the midterm, and that it is used for security-sensitive communication including account recovery, and privacy-related communication, not improving it is negligent.

Even if email cannot be protected from a powerful state adversary (although, I think tools designed with security in mind rather than bolted on later could), it makes sense to try to improve the status quo based only on defense in depth and harm reduction arguments.

For years, the OpenPGP ecosystem survived thanks to Werner Koch’s work on GnuPG. But, his shoestring budget didn’t allow him to take up the challenge to reinvent OpenPGP’s UX:

It baffles me that nobody has instead picked up the challenge of taking the PGP/GPG cryptosystem and making it more usable. That seems like an incredibly valuable project that also makes great use of the skills of the sorts of people that tend to want to work on privacy software.

- Thomas PtacekThe last few years, however, have seen a resurgence of interest in OpenPGP. We, Sequoia PGP and pEp, are just one group rethinking not only the architecture of OpenPGP tooling, but also the user experience. A few of the others include ProtonMail, Mailvelope, and FlowCrypt.

Start using encrypted email.

Copyright (c) 2018-2023, p≡p foundation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Follow us on Mastodon.

Template by Bootstrapious.

Ported to Hugo by DevCows.

Images by Ingo Kleiber, and Robert Anders.